Many Modular Megaprojects

I came across this super interesting article while researching megaproject efficiencies: Make Megaprojects More Modular by Bent Flyvbjerg. And it got me thinking. Firstly, great title. Love the alliteration.

And secondly, for context, Flyvbjerg is the patron saint of Megaproject Bad, with a particular pithy statement encapsulating megaprojects within the so called Iron Law of Megaprojects: Over budget, over time, under benefits, over and over again. Flyvbjerg is a frequent witness in megaproject inquiries, and a well-known author and critic of megaprojects. But he (and other critics) has never said good megaprojects don't exist. And we'll look at both bad (and very bad) and some good (and very good) megaprojects in this article. Honestly, just go read the article with the lovely alliterative title. If you want a summary though, plus some discussion on how this may relate to China's record of megaproject success, read on.

Flyvbjerg says replicable modularity in project design and speed in iteration are key to megaproject success. And the examples he gives are:

Positive:

-

Tesla's Nevada Gigafactory. Its modular design where people could learn from the delivery of one to improve the delivery of the next helped Tesla start production earlier and lower cost overruns compared to a typical complete the full factory process.

-

Dove satellites. Its modular approach using modules consisting of standard commercial off-the-shelf components for electronics and structure, helped them keep cost and delivery time low.

Negative:

-

Japan's Monju Nuclear Plan. This project was next level terrible. It generated electricity for 1 hour across 34 years and after $12 billion. It'll cost another $3.4 billion to decommission. Main reasons: everything at Monju was the opposite of modular, scalable, and repeatable, and the more people learnt, the more obstacles and necessary work they identified.)

-

Eurotunnel. This megaproject had costs overruns of 80% (construction) and 140% (financing). Revenues were late (obviously) and this project had a negative (negative!) rate of return of -14.5%.

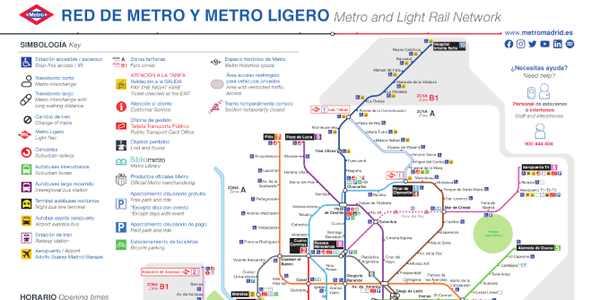

The largest case study, though, is on the Madrid Metro.

The Madid Metro achieved its objectives at 'half the cost and twice the speed of industry averages'. How did they do this?

This project was characterised by simplicity - no monument building, no extra unproven innovative technologies, only using tried and tested techniques and technologies, and speed - iteratively getting better, replication, and throwing resources at getting the job done in a parallel rather than series manner. Interesting aside on the speed part, this project was the first to move away from hiring one or two tunnel boring machines (TBMs) and teams and rather hire the optimal number to essentially get the tunnel bored in the shortest period of time possible. It sounds rather obvious now we think about it, but this went against established wisdom. Other points of interest: these TBM teams got their competitive spirit on (but in a healthy way) and project leadership convinced residents to accept 24/7 drilling for 3 years when given an option between that or 8 years of business hours construction. Again, sounds obvious in retrospect, but man, the results are pretty good!

So, the elements of successful megaproject execution seem to be:

-

Simplicity enabling learning by doing and iterative repetition

-

Iterative repetition and scalability unlocking speed and continuous improvement by doing, doing better, faster, and larger

-

Speed (pace is pace yaar) minimizing cost and schedule overruns

And now, to China. China has had an infrastructure boom, the size, scale, and sheer imagination of which is unprecedented in history. I posit the very nature of this construction boom leads to significant economies of scale (literally millions of trained workers), labour force expertise (workers increasingly familiar with megaprojects), iterative repetition and scalability (you get a metro! You get a metro! You also get a metro! Repeat for high-speed rail, hospitals, roads, power lines, housing ....), and speed (all these improved factors mean projects get delivered faster). (other factors identified by a British urban planner here). And it's not just infrastructure, the Chinese economy has a surfeit (relative to anaemic, manufacturing-leery, service-heavy developed economies) of engineers, technicians, labourers, and producers who can solve manufacturing problems faster than you can recall the good old days when western economies had these abilities in house. And its cheaper too (which is why these abilities were driven off-shore...)

Back to megaprojects. A 2016 article by Ansar et al that compares Chinese megaprojects to megaprojects in 'rich democratic countries', while overwhelmingly negative specifically about China's infrastructure spending and snooty about China's delivery advantage vis-à-vis other rich countries, does acknowledge that Chinese megaprojects are significantly better on construction time (4.3 years vs 6.9 years) and schedule overrun (5.9% compared to 42.7%).

So, I'll propose another element to the success factors in making megaprojects successful. In addition to making them modular, do more of them. Slightly tongue in cheek, yes. But overall, I'd say the infrastructure, construction, and project management expertise unlocked by the mere act of doing a project, if repeated across an economy, may drive significant network effects, just like Chinese manufacturing has leveraged network effects in becoming simply irreplaceable in the global economy (if the rest of the world wants to have low-inflation good times, that is..)

(Do Many Megaprojects and) Make Megaprojects More Modular. Less of a ring to it, but I think we're on to something.

P.S.

I am not suggesting doing projects and megaprojects for the sake of doing them, I'm noting though, a big infrastructure push (as badly needed in Canada with its aging assets, among other advanced nations) will benefit from learning from China's infrastructure experience. I also note my analysis, rough as it is, exclusively focuses on project delivery, not project finance. Lastly, the overwhelmingly negativity of the Ansar et al article can be tl:dr'd as: infrastructure does not create economic value and China does not have a distinct advantage in its delivery (China's infrastructure boom came after China already achieved economic growth and is overwhelmingly debt-fueled that has required monetary policy to pull off -- but is this a juggle?).